Barbara Schmidt-Abbey (Open University)

Joan O’Donnell (Maynooth University)

Kirsten Bording Collins (Adaptive Purpose)

Introduction

The title of the 14th European Evaluation Society’s Biennial conference in Copenhagen in June 2022 posited that evaluation finds itself at a watershed and called for “actions and shifting paradigms in challenging times”.

At the time of the conference, and when readers read this, nobody can be left in any doubt that we indeed live in challenging and uncertain times that require an urgent shift in our thinking and doing as evaluators. The ongoing pandemic, war raging on the European continent, a looming energy and food crisis amidst rampant inflation, and extreme weather events are stark signs of ‘systems failures’ that are becoming increasingly harder to ignore and stay complacent about.

Picture 1: Photo of (L-R) Kirsten Bording Collins, Barbara Schmidt-Abbey and Joan O’Donnell

They hammer home that we are indeed living in a much cited ‘VUCA’ world (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous). The issues evaluation and evaluators are faced with are often characterised as ‘wicked problems’ (Rittel and Webber, 1973), or even worse, as ‘super-wicked problems’ (as referred to in Hans Bruyninckx’s keynote speech at the conference). Instead of simple, solvable problems, we are dealing with ‘messes’ (Ackoff, 1974). The traditional methods and tools that worked well in ‘normal times’ are being exposed as woefully inadequate.

Contributions at the previous EES conference in 2018 in Thessaloniki, such as Thomas Schwandt calling for ‘post-normal evaluation’ (Schwandt, 2019), are even more urgent now: we truly find ourselves at a watershed, where it becomes more and more obvious that traditional evaluation methods, approaches, institutional arrangements and mindsets are no longer sufficient to meet the nature, urgency and scale of the challenges, and that ‘business as usual’ in evaluation is no longer an option. It may even be part of the problem as was suggested throughout several conversations at the conference.

How then can we as evaluators rise to this challenge, and bring about the proclaimed needed ‘actions’, and ‘shifting paradigms?’

The fields of systems thinking in practice, and of second-order cybernetics can provide us with some useful concepts that can help.

The shifts we need to see are interdependent

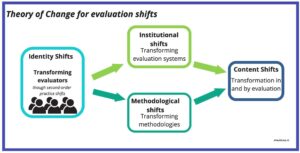

The conference themes suggest four interdependent necessary shifts to bring about this change: institutional, methodological, identity and content shifts (see Fig. 1).

These can be arranged as a proposed ‘theory of change’[1], which we use to structure this contribution:

- Identity shifts: it is first and foremost necessary for evaluators to transform from within, by turning our attention to ourselves as evaluators, and the roles we play in evaluating. The other necessary shifts are facilitated by this introspection.

- Institutional shifts: the institutional arrangements within which evaluations are situated, commissioned, conducted and used must be transformed

- Methodological shifts: transforming methodologies, and how they are used

- Content shift: the above shifts contribute collectively to a ‘content shift’, where situations are being transformed by evaluation, and evaluation itself is also transformed, at another level.

[1] This draft ToC is an initial framing and is open to further discussion and development.

Fig. 1: A theory of change for evaluation shifts based on EES 2022 conference themes

The need to make second-order shifts

As practitioners, we can easily be overwhelmed by the magnitude of the challenges we face. We may ask ourselves, “how can we possibly manage to tackle all these shifts, when the stakes are high, and action and change are urgent?” To overcome a potential feeling of dread and paralysis, we propose taking inspiration from the fields of systems practice and cybernetics by taking a ‘second-order’ approach.

The most useful shift we can make is to see ourselves as vested stakeholders in the evaluation, with power and agency. For example, this includes questioning framings for Terms of Reference (second-order identity shift) rather than fulfilling contracts using evaluation ‘tools of the trade’ instrumentally and acting like a tradesperson (first-order thinking). The shift can be understood as the difference between doing something unreflectively, routinely, and doing something with a higher order purpose in mind. A second-order approach involves critically engaging in a dialogue with commissioners at the initiation stage about the Terms of Reference, in order to ensure that the purpose of the evaluation is exposed and questioned, and with view to creating favourable conditions of systemically desirable changes to the situation within which the evaluation takes place. ‘Being’ an evaluator in this mode involves ethics: acknowledging wider consequences of the work done (evaluator as craft artisan/bricoleur).

Failure to reflect on our own part in evaluations can too often result in carving up kittens and not just cake, without intention to do harm. While evaluating the success of a cake invariably involves cutting it up and eating it, we sometimes do this inadvertently in complex systems also. It is time to let go of dissecting living systems in the hunt for impacts that can be elusive, and instead shift attention to ensuring that projects are creating the right conditions for change.

Identity shifts: What do we do when we do what we do?

As we can see, if we want to successfully contribute to the desired shifts, it is first and foremost necessary for us as evaluators to transform ourselves from within.

As proposed in the theory of change (Fig. 1), we suggest that it is fundamental to turn our attention to ourselves as evaluators, and the roles we play in evaluating. Change must start with us ourselves. This also requires that we begin to see ourselves as part of the system we are evaluating.

Evaluator inclusion as part of the system is an essential and necessary precondition for such an identity shift. In a recent award-winning paper, Cathy Sharp (2022) suggests that the time for this approach has arrived.

This idea is taken up in Barbara’s Think Tank session “Being evaluation practitioners in a volatile and uncertain world: What do we do when we do what we do?” which is part of her ongoing doctoral research, and builds on some key ideas expressed in Schmidt-Abbey et al. (2020).

The title cites a phrase coined by Humberto Maturana, who invites us to critically reflect about our practice in asking “What we do when we do what we do”? (Ison, 2017:5). This is essentially a second-order question. When speaking about ‘evaluation practice’, the focus is therefore on the practitioner.

The different interactions we juggle when doing evaluations systemically can be brought to life using a playful heuristic of an evaluator as a juggler, simultaneously juggling four balls: the B ball (Being a practitioner), the C ball (Contextualising evaluation to situations), the E ball (Engaging in specific situations when conducting the practice of evaluating) and the M ball (Managing an overall evaluative performance including relationships with stakeholders).

Picture 2: Image from Barbara’s Think Tank: Juggling in action! (Photo credit: thanks to Laetitia Dansou)

Think Tank participants jointly explored three questions, which may be added to Sharp’s (2022) provocative questions:

- How do evaluation practitioners engage with complex situations of change and uncertainty?

- How do evaluators reflect on the choices and use of approaches and methods in these situations?

- What opportunities exist for evaluators to make a ‘second-order practice shift’ in such situations?

Methodological shifts

Methodological approaches to evaluation need to shift from sustaining business as usual (first- order) to encouraging innovation and continuous viability in the context of rapid and continuous change. Systems thinking has many tools that can support this.

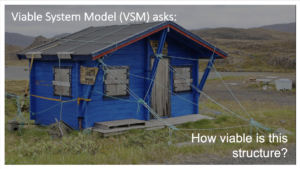

Two tools worth noting are the Viable Systems Model (Stafford Beer 1979) – which establishes the conditions necessary for a programme to sustain viability over time (see fig 3), and Critical Systems Heuristics (Ulrich and Reynolds 2020) which explores the boundaries around a programme and questions the gap between how things are and how they should be. Both are therefore concerned with both evaluating the current state of affairs and designing better alternatives. While VSM emphasises the importance of sporadic monitoring processes, CSH asks questions relating to values and ethics – key considerations for any evaluation activity.

In her conference presentation “Evaluating the enacted transformation of Irish disability services from face-to-face to virtual services using the Viable Systems Model”, Joan proposed VSM as a way of getting to the heart of processes that support developing practices that help us in ‘learning our way out’ of those moments when expertise, habit and competence fail us amidst the complexity and uncertainty we are faced with (Raelin 2007: 500 in Gearty & Marshall 2021). Not only can VSM assess the value that a system offers the environment, it stress-tests the interrelationships between different parts of the system, challenging siloed thinking, lack of coordination either internally or between projects as well as the deployment of resources and governance. These are all essential components of a second-order evaluation.

Picture 3: Image from Joan’s Conference paper: Evaluating the enacted transformation of Irish Disability Services from Face-to-Face to Virtual Services using the Viable Systems Model (Photo credit: Mark König on Unsplash)

Contents shifts

Content changes also require a focus on making sense of complexity in real time and learning forward to guide future action relevant to the future we are creating. It was also the focus of Joan’s workshop on her doctoral research “Shifting Ground: psychological safety as a systemically desirable way to evaluate the development of resilient inclusive and equitable communities”, which explored the enacted response of disability service teams that developed virtual services during the pandemic. Her findings suggest that the degree to which they were able to be fully present and engaged contributed to a felt sense of psychological safety and supported personal experiences of meaning-making at a particularly stressful time for both staff and people with disabilities. Her presentation suggested psychological safety, if reframed as a systemic construct, becomes a core condition for creating resilient inclusive communities, and thus offers a valid focus for evaluation.

This is in contrast to a more first order framing of psychological safety as a way in which leaders think and act to create candor in teams in the interests of innovation and productivity (Edmondson 2019). It can therefore serve as an example for a content shift brought about by taking a systemic and second-order, rather than a systematic traditional first-order research and evaluation approach.

Institutional shifts

An institutional shift concerns the transformation of the arrangements, structures and norms within which evaluations are situated, commissioned, conducted and used.

Amongst others, Martin Reynolds’s presentations reviewed earlier work (Reynolds, 2015) by identifying new opportunities to ‘break the iron triangle’ in which evaluation can be trapped, by shifting to a more ‘benign evaluation-adaptive complex’ in institutional arrangements, to enable more purposeful evaluations, and suggesting value for ‘mainstreaming evaluation as public work’.

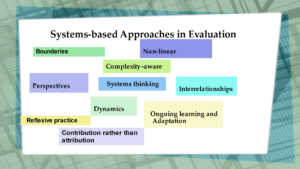

Another angle to institutional shifts was explored in the Think Tank “Mainstreaming System-based Approaches in Evaluation: What is our Role as Evaluators?” led by Kirsten, which explored the question of what the role of evaluators might be in ‘mainstreaming’. The idea of ‘mainstreaming’ systems-based approaches can be seen as a way to institutionalise the desired transformation of evaluation, in the way evaluations are done.

This Think Tank intended to share experiences and generate discussion on how we can better integrate systems-based approaches in evaluation. It began with a grounding to come to a common understanding of what we mean by ‘systems-based’ approaches, for which the following characteristics were proposed:

Picture 4: Image from Kirsten’s Think Tank: some characteristics of systems-based approaches in evaluation

Although there are advances to incorporate systems-based approaches in evaluation, including important efforts such as Developmental Evaluation and others, we would argue it is still at the fringes and is not mainstream in evaluation.

The general consensus among participants in this Think Tank was that we have a long way to go, and much education, advocacy and capacity-building is needed to integrate and mainstream system-based approaches in evaluation. We have to start with a ‘mind shift’, and we need to embed systemic approaches in the design and planning of evaluations. It appears that some progress is happening in this regard on the ground, for example, where cross-organisational teams are embedded across processes instead of evaluation offices in large organisations, even if this is still only largely taking place at the programme level, and not organisation-wide.

What could be done to better integrate and mainstream systems-based approaches and what could our role as evaluation practitioners be in this process? Many ideas and suggestions were offered in a lively brainstorming exchange. Some of these included making a clear business case for the use of systems approaches, clearly spelling out the What, Why and How, and using language that resonates with the appropriate audiences. The role of evaluation managers is also seen as critical vis–a-vis commissioning and acting responsibly and ethically. Evaluators need to reinvent themselves, and evaluation needs to become embedded within projects and programmes.

The consensus was that we cannot do this alone and need instead to join forces towards mainstreaming systems approaches in evaluation, in order to prompt the necessary institutional shifts.

Towards institutionalising systems approaches in evaluation practice – where to next?

In order to progress the institutionalisation of systems thinking in evaluation practice, the idea emerged in Kirsten’s Think Tank to establish a new Thematic Working Group (TWG) within EES on ‘evaluation and systems thinking’, to convene a more systematic as well as systemic space for evaluators / members of EES interested in mainstreaming systems thinking into evaluation practices.

Therefore, we plan to develop a proposal to be brought to the Board of EES that is being drafted by a group of volunteers arising from the workshop. A dedicated TWG devoted to systems approaches in evaluation could contribute towards bringing fragmented efforts together, be a forum for exchanges and developments, and share inspiring examples of practice leading to mainstreaming and institutionalising systems approaches in evaluation practice.

It is time to shift the ground. Join us!

Contact any of us!

- If you want to know more about the planned TWG and would like to contribute, please contact Kirsten at kbcollins@adaptivepurpose.org.

In parallel, the presented doctoral research continues further. For more information, please contact:

- Barbara at barbara.schmidt-abbey@open.ac.uk– if you are an evaluation practitioner dealing with situations of complexity and uncertainty, you can still contribute to Barbara’s research with an in-depth interview, and watch the space for forthcoming results.

- Joan at Joan.odonnell.2020@mumail.ie. – for further information on methodological approaches and psychological safety. Joan’s contribution has emanated from research supported in part by a Grant from Science Foundation Ireland under Grant number 18/CRT/6222.

References

Ackoff, R. (1974) Redesigning the future. New York, Wiley

Beer, S. (1979) The Heart of the Enterprise. New York, Wiley

Bruyninckx, H. (2022) Keynote speech at EES 2022, 8 June 2022

Edmondson, A. (1999) Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative science quarterly, 44(2): 350-383

Edmondson, A. (2019) The Fearless Organisation. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons

Gearty, M. R., & Marshall, J. (2021) Living Life as Inquiry – a systemic practice for change agents. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 34(4): 441-462

Ison, R. (2017) Systems Practice: how to act – in situations of uncertainty and complexity in a climate-change world. 2nd ed. London, Springer

Rittel, H. and Webber, M (1973) Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci (4): 155-169

Reynolds, M (2015) (Breaking) The iron triangle of evaluation. IDS Bulletin 46: 71–86

Schmidt-Abbey, B., Reynolds, M., Ison, R. (2020) Towards systemic evaluation in turbulent times – Second-order practice shift. Evaluation, 26(2): 205–226

Schwandt, T. (2019) Post-normal evaluation?, Evaluation, 25(3): 317–329

Sharp, Cathy (2022) Be a participant, not a spectator – new territories for evaluation. The Evaluator (Spring 2022): 6-9

Ulrich, W., Reynolds, M. (2020) in M Reynolds, S. Howell (eds), Systems approaches to making change: A practical guide, Springer, London.