Author: Ian Thomas, Head of Arts Research & Insight at British Council

In a 2018 the British Council explored the notion that cultural heritage could contribute to inclusive growth. The report shares findings from a sector consultation and international research suggesting that when people or communities are given the opportunity to engage with, learn from and promote their own cultural heritage, it can contribute to social and economic development.

Cultural Heritage for Inclusive Growth adopts a cultural relations approach to facilitate the exchange and collaboration among local cultural heritage stakeholders and between the UK and countries overseas. The programme explores how cultural heritage can act as a catalyst for change and strengthen the British Council’s ability to enable longer-term conditions for inclusive and sustainable growth in different cultures, communities and countries.

Cultural Heritage for Inclusive Growth, an action research initiative exploring ways in which community cultural heritage can bring prosperity and wellbeing to local life. During its pilot phase in Colombia, Kenya and Viet Nam the programme reached over 44,000 people, generating significant impact through its locally led approaches. Through pilot projects in Colombia, Kenya and Vietnam, the action research programme explored cultural heritage for inclusive growth as a global concept with local solutions. The projects are community- and people-led and are devised and managed with local partners on the ground, supporting local communities to promote their own cultural heritage, leading to economic growth and improved social welfare.

The programme aims to continually explore and develop a people-centred approach to cultural heritage for inclusive growth. This includes an ethos of promoting wider inclusion, diversity and creating value to generate growth and prosperity as felt by those closest to their cultural heritage, a broad range of stakeholders, the population and wider ecosystem. Hilary Jennings argues that ‘people-centredness’ could be understood as composed of two elements: process and power. That process without the sharing of power was at best cosmetic while power-sharing without process was unlikely to yield best results.

The evolution of Cultural Heritage for Inclusive Growth M&E and the learning, working with our evaluation partner TSIC, has provided valuable insights into how Cultural Heritage for Incluisve Growth M&E could be more fit for purpose, that is, acting based on the core way of working in the programme: people centred.

People-centred evaluation significantly differs from conventional M&E in that the community, beneficiaries and people involved in designing and implementing the project, are involved in M&E throughout the project’s duration. Benefit of participatory M&E is that it can demonstrate and improve accountability to targeted individuals, groups or communities (sometimes known as downwards accountability). Moreover, this evaluation tends to be carried out at multiple stages of the programme, and not just at the end.

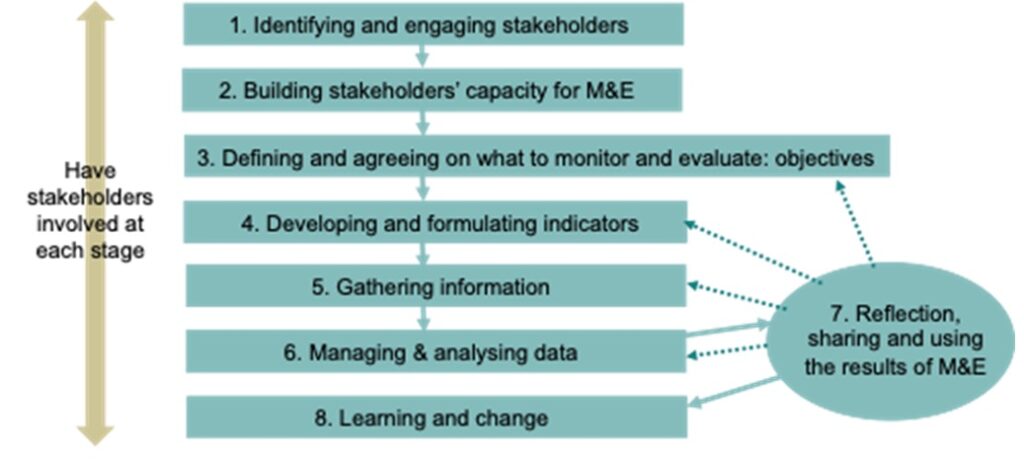

The implementation of the people-centred evaluation starts with identifying and engaging with stakeholders, followed by building their capacities for M&E. This is mostly followed by co-defining the scope of the evaluation and deciding on what is worth evaluating and how. The next step is to design and formulate relevant indicators and start gathering data that can help in understanding the impact. A crucial step is then to start reflecting on the data and sharing the results of M&E to inform future learnings and change processes. This activity can benefit from the self-reflection of the beneficiaries and other stakeholders. Thus, the process is characterised by the active engagement of stakeholders at each stage of people-centred evaluation.

In comparison to conventional evaluation, while people-centred evaluation adopts mix methods in data collection, it often embraces participatory and/or creative methods, making evaluation more engaging for people to interact with.

Figure 1 People centred evaluation process adapted from TSIC

Just as inclusion was identified as the underlying tenet of people-centred evaluation diversification could be argued as the key driver for the value of people-centred evaluation. A diversification of perspectives through the inclusion of different participants is often seen as an important mechanism for identifying gaps in knowledge that professional evaluators may have been blind to. Additionally, the relevancy and prioritisation of M&E, and the efficacy of subsequent interventions, is seen to be improved through the inclusion of diverse perspectives.

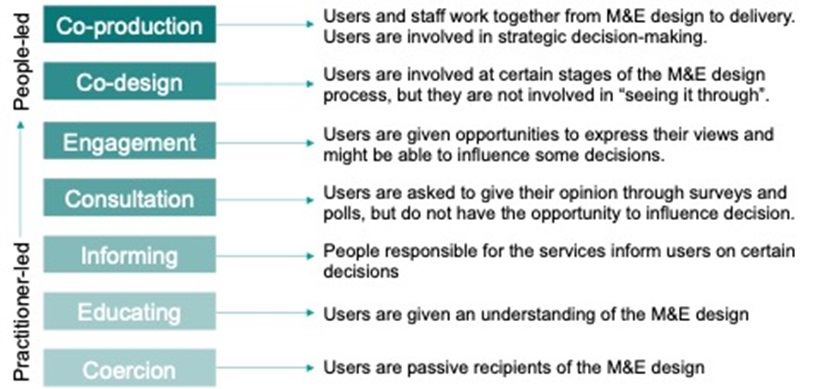

Like most people-centred approaches, people-centred evaluation is not easy. It takes time, resources, and a committed willingness to let go of control over decision-making. Ideally, people and stakeholders should be involved across all stages of the evaluation. Considering time and resources available, an evaluation could reflect on the level of co-production suitable at different stages of evaluation.

Figure 2 shows a co-production ladder, a tool to consider how to collaborate with the users (or people/stakeholders impacted by the intervention).

Figure 2 Co-production ladder adapted from TSIC.

There is an urgent need for more meaningful and participatory M&E approaches in the international development sector to help support more equitable, inclusive and sustainable interventions. To implement people-centred evaluation, evaluators and project teams should understand and explore:

- Participant ownership and timing: Evaluation is oriented to the needs and capacities of the participants and has to start from the very beginning.

- Openness and reflexivity: Participants meet to communicate and negotiate about what will be evaluated, how and when data will be collected and analysed, what the data actually means, and how findings will be shared. Input from participants should be balanced.

- Flexibility and transparency: Flexible design and a mix of methods should be adopted. Evaluation procedure should be documented and made accessible to everyone involved.