The monumental challenge posed by the Greek debt crisis required financial assistance on an almost unprecedented scale. John Goossen and Kari Korhonen, as members of the team that have produced a landmark independent evaluation of that financial support, argue that their work carries important lessons for the future of evaluating such crises and the responses to them.

Authors: John Goossen and Kari Korhonen

The second crisis assistance evaluation of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the euro area sovereign rescue fund, highlights several lessons for future crisis response. This exercise, led by former European Commission Vice-President Joaquín Almunia, concentrated on the provision of stability support to Greece from 2012 to 2019. Mr Almunia made five headline recommendations, each with sub-points. Together with the resources of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the support offered to the country became historic in size. The rescue evolved into a complex political, social, institutional and economic endeavour, which needed to overcome extraordinary domestic and international challenges.

Providing emergency assistance involves a multitude of participants and mandates that affect both the objectives and procedures. In these circumstances, a cooperative and coordinated approach becomes a must. In the Greek case, assistance became a multi-year endeavour. The relevance and success of such programmes are not assessed solely on the participating institutions’ objectives but also on the impact of the reforms on a complex socio-economic fabric. These outcomes materialise at different times and are strengthened or weakened by other activities in society, international financial markets or the world economy. A crisis environment also creates profound uncertainty and social dislocation, which disrupts normal practices and complicates causal analysis.

Against that backdrop, it is no surprise that the conduct of the programmes became politically sensitive. How do you evaluate such a vast and sensitive endeavour?

- Protecting the evaluation’s independence

This evaluation exercise was anchored to the High-Level Independent Evaluator, supported by an expert team of many nationalities and diverse areas of expertise. An advisory group of senior evaluators with backgrounds in other international financial institutions also provided advice at pivotal stages. In addition, separately prepared background papers informed the evaluation and were published in conjunction with the report itself.

Given the high stakes, the ESM took precautions against real and perceived conflicts of interest. For this purpose, the Evaluator reported to the highest ESM governing body and care was taken to assign a support team that had had no involvement in the assessed activities. The team conducted surveys and interviews to collect a wide variety of views and information. The reporting lines were clearly defined to preserve the team’s independence.

Additionally, the team ensured the Evaluator’s ownership of the evaluation conclusions through iterative discussions and reviews. He participated in high-level interviews, studied interview summaries and the team’s analyses. While report drafting was collaborative, the ensuing recommendations are exclusively his.

External consultants also strengthened the team’s analytical independence, as did its constant access to a senior external adviser who chaired the aforementioned group of external advisors.

- Theory of Change as corner stone

The evaluation design followed standard evaluation criteria and incorporated pre-assigned themes that aided in the development of a matrix of evaluation questions. In the preparatory phase, an evaluability assessment was conducted to test the team’s understanding of the programme framework and determine how realistic the work plans were.

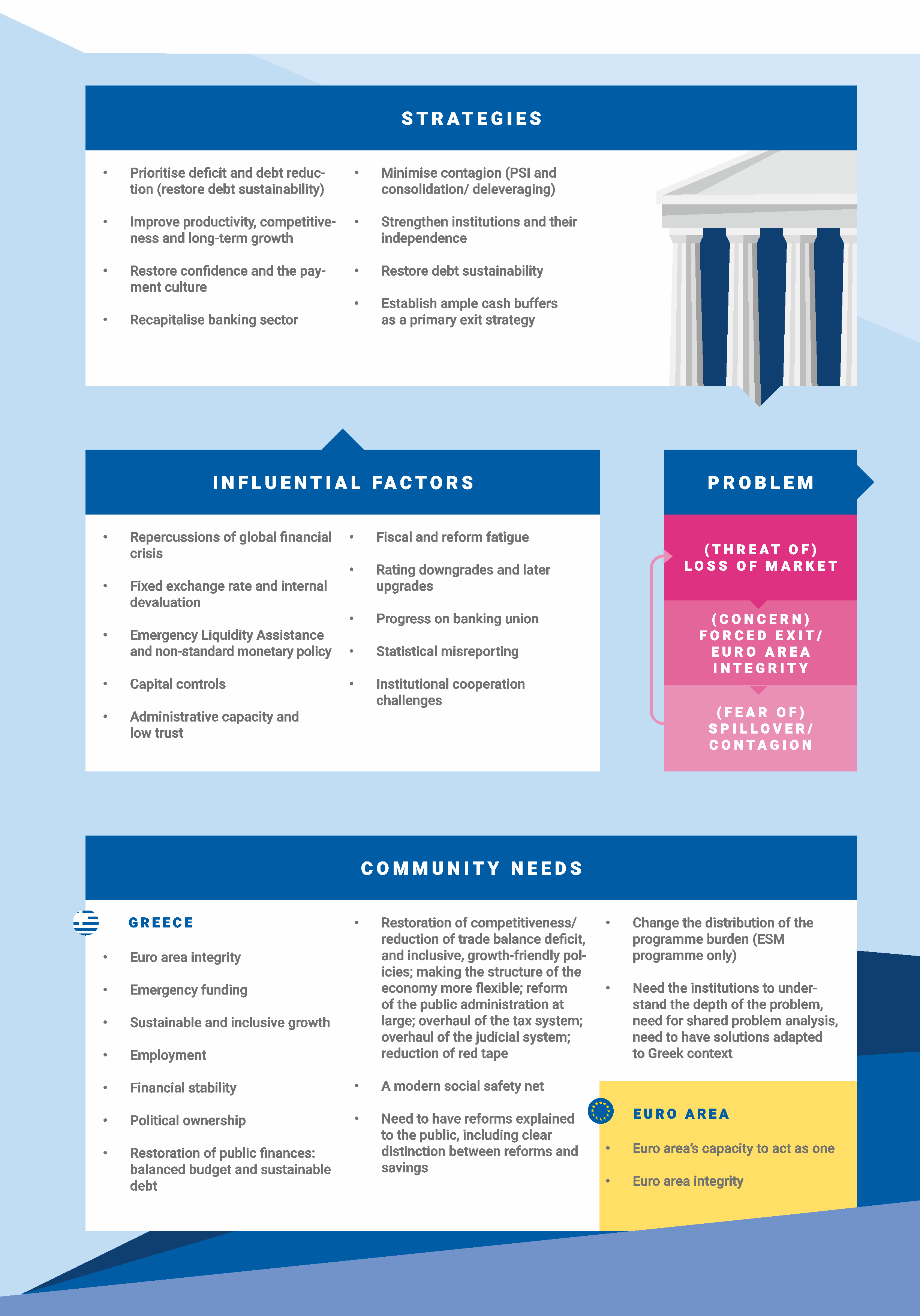

In the absence of an existing Theory of Change (ToC) for the Greek assistance programmes, the team put considerable effort into developing one. A common instrument in the development community for evaluation and programme design, it sharpens the focus on more detailed aspects of the programme and helps to define more specific evaluation questions. The model (see graphic below) includes a description of the central problem to be addressed by the financial assistance to Greece, along with the programme strategies and their underlying assumptions. The ToC also incorporates the main contextual factors influencing the intervention, the principal effects and unintended consequences, and the community needs that described the external expectations towards the intervention.

The main limitations of applying the Theory of Change to Greek financial assistance were the deep complexity of the successive programmes, the evaluation’s wide scope and the long time span covered, in which a number of the components (programme strategies, assumptions, context, even the central problem) experienced various degrees of change. Still, it provided a valuable evaluation tool that could also inform future programme design, and subsequent evaluation.

Figure. Theory of change for Greek financial assistance

- Ensuring broad and relevant input

The Greek evaluation drew from a broad set of source material ranging from official programme documents, evaluations by other institutions, academic papers as well as stakeholder interviews, survey material, and commissioned background papers.

To avoid bias, the team gathered views from a representative group of sufficiently informed and diverse interviewees across institutions, nationalities, disciplines and political affiliations. The team was able to consult experts and decision-makers at a variety of levels and attempts to reach out to specific experts in academia, the media and political parties were almost always successful. Similarly, the team enjoyed access to a vast amount of information; key pieces of information that could not be immediately accessed to corroborate certain findings usually found a way into the report via another route. Internal decision-maker interviews were only conducted after the completion of external interviews so as to avoid bias. Lastly, the role and standing of the High-Level Independent Evaluator should not be underestimated in ensuring broad and relevant input.

- Triangulation of findings

The mixed-methods approach played an important part in triangulating the findings from various sources to corroborate the main narrative while also considering contradictory information and dissenting opinions. The team analysed interview transcripts and available documentation in a qualitative data analysis programme that helped to pool the input on relevant topics. Team discussions and reviews by the Evaluator helped to detect the cross-cutting interconnections and themes.

The evaluation of efficiency and effectiveness requires a mix of quantitative and qualitative research. While qualitative sources are important for a deep understanding of the events and perceived reasons for certain developments, quantitative sources underpin our understanding of large economic and societal developments. Access to detailed financial data and knowledge of procedures supported the assessment of efficiency in the Greek assistance. The centralisation of banking supervision in the euro area has also improved the availability of comparable data for the sector while data on social developments still seem to come with considerable delays, hampering any early evaluation that stretches beyond the financial sector such as ours.

The team diligently collected and triangulated findings to synthesise them and reached conclusions through reiterative steps to ensure consistency. These fed into the recommendation building process. The Evaluator’s standing ensured the recommendations’ relevance to the decision-makers. His relative detachment also allowed him to distance himself from perceived taboos.

- Ensuring stakeholder engagement

The final step in the inference stage is to arrange interim consultations with stakeholder groups to collect feedback on the evaluation outcomes and conclusions, and draft recommendations. At this point, stakeholders have an opportunity to ensure a high quality evaluation. In this evaluation, we constantly emphasised the purpose to learn lessons for the future and our genuine interest in our interlocutors’ expert views on and unique insights into events and developments they deemed relevant. The vast majority appreciated the opportunity to share their narrative, subject to confidentiality. This trusting relationship was required to break through the barrier of institutionally accepted truths, already accessible in existing publications, and was a key ingredient in a truly compelling report.

Basis for learning

This evaluation model showed that a qualified High-Level Independent Evaluator supported by a diverse evaluation team makes in-depth and complete coverage possible. Rigorous working methods and safeguards for independence enabled the publication of a frank assessment.

The real success of the evaluation nevertheless depends on how effectively it manages to contribute to institutional learning, which in the European context stretches beyond a single organisation. Crisis resolution arrangements cannot predict when they will be called upon next, but they can prepare themselves for future action by creating established procedures and predefined analytical and policy frameworks to define strategic objectives. Rather than prescribing a one-size-fits-all blueprint, this should allow to better manage the transition from a crisis situation to regular programme management to post-programme engagement. Applying the know-your-customer principle to institutions involved in country programmes also merits consideration: investing in stakeholder analysis could yield significant results in terms of programme effectiveness and credibility. A robust monitoring framework and continued policy advocacy can safeguard the adjustment gains and ensure their sustainability.

Disclaimer: The authors played key roles in the evaluation team that conducted the second ESM evaluation. Technical appendix to the evaluation report provides more details on the conduct of the evaluation. The views expressed in this blog do not necessarily represent those of the ESM or ESM policy. No responsibility or liability is accepted by the ESM in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented in this blog.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Evaluation Society.